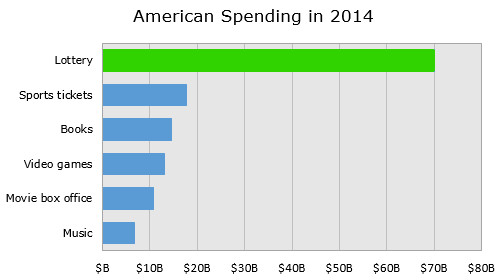

Every year, Americans spend a mind-blowing $70.1 billion on the lottery. That works out to an average of $630 per household, representing more money spent on gambling than on books, sports tickets, recorded music sales, video games, and the movie box office – all combined!

This is according to data visualization expert Max Galka, who published a series of posts and visualizations on the economics of the lottery in his Metrocosm blog. The numbers he provides are both astounding and alarming, ultimately making a convincing case that the lottery is a regressive and inefficient tax on some of the nation’s poorest people.

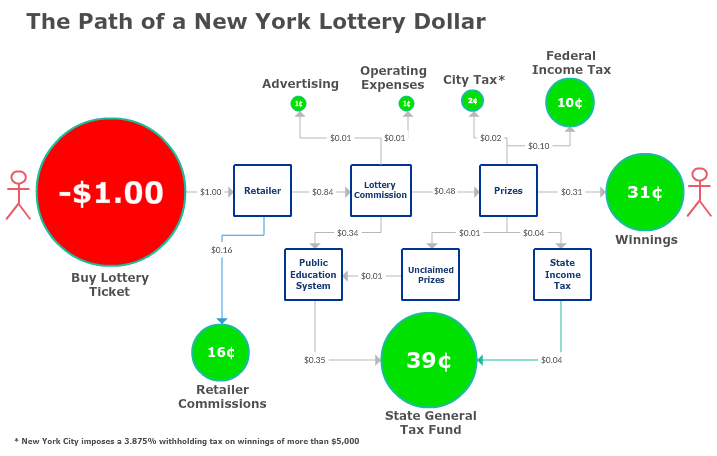

Let’s start with the economics. Here’s the math on the New York Lottery, which is a starting point to understanding the inefficiency behind lottos in the first place:

To sum up the math:

- 51% of each dollar goes to tax revenue: federal, state, and municipal.

- 18% goes to covering expenses, such as advertising or retailer commissions. This is the part that makes the process inefficient.

- 31% of each dollar actually goes to the prize money, and that basically sums up the terrible odds behind winning in the first place.

In other words, for every $3 spent on the New York Lottery, less than $1 is paid out to winners, while the other $2 is going to expenses and tax revenues.

The House Advantage

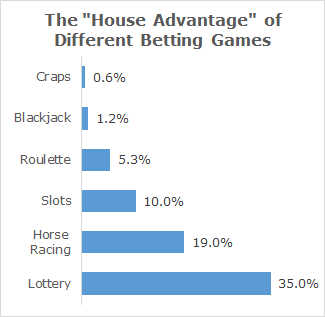

As Max notes in one of his posts, the lottery itself is not a tax – but the artificially inflated price of lottery tickets ultimately ends up as an indirect excise tax:

Choosing to play the lottery is voluntary. But much like sales taxes, the inflated price of lottery tickets is not.

It is illegal for anyone but the state to run a lottery. So unlike casinos, which face competition from other casinos, lotteries operate as a monopoly, so they can set their pricing artificially high, or equivalently, their payout rates artificially low.

While it is true that many people stay away from lottery tickets because the odds are not in their favor, there are groups of people that are far less fortunate. They and their families bear the brunt of inefficient lotto economics, as well as the house advantage.

Who’s Buying Lottery Tickets?

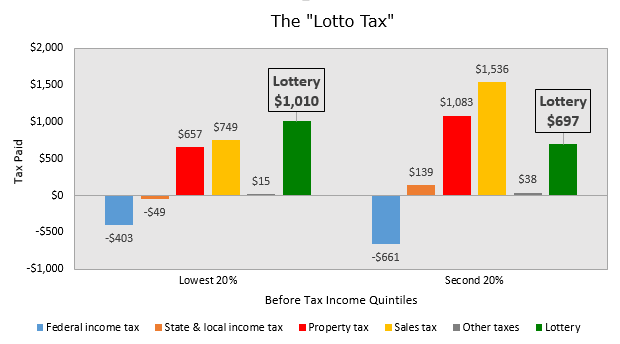

Lottery sales follow the 80/20 rule. It turns out that 82% of all sales come from 20% of the players.

Many of these players are compulsive gamblers, and many also come from lower income brackets.

In this post, which includes some key assumptions, Max shows that the “lottery tax” is a significant burden for many low-income households even in contrast with other taxes:

Want more perspective on lottery ticket sales? We previously showed a similar comparison of U.S. consumption numbers in real-time.