Which Countries are Mapping the Ocean Floor?

Our vast and complex planet is becoming less mysterious with each passing day.

Consider the following:

- Thousands of satellites are now observing every facet of our planet

- Around three-quarters of Earth’s land surface is now influenced by human activity

- Aircraft-based LIDAR mapping is creating new models of the physical world in staggering detail

But, despite all of these impressive advances, our collective knowledge of the ocean floor still has some surprising blind spots.

Today’s unique map from cartographer Andrew Douglas-Clifford (aka The Map Kiwi) focuses on ocean territory instead of land, highlighting the vast areas of the ocean floor that remain unmapped. Which countries are exploring their offshore territory, and how much of the ocean floor still remains a mystery to us? Let’s dive in.

What Do We Know Right Now?

Today, we have a surprisingly incomplete picture of what lies beneath the waves. In fact, if you were to fly from Los Angeles to Sydney, the bulk of your journey would take place over territory that is mapped in only the broadest sense.

Most of what we know about the ocean floor’s topography was pieced together from gravity data gathered by satellites. While useful as a starting point, the resulting spatial resolution is about two square miles (5km). By comparison, topographic maps of Mars and Venus have a resolution that’s 50x more detailed.

As the map above clearly illustrates, only a few large pieces of the ocean have been mapped—and not surprisingly, many of these higher resolution portions lie along the world’s shipping lanes.

Another way to see this clear difference in resolution is through Google Maps:

As you can see above, these shipping lanes running through the Pacific Ocean have been mapped at a higher resolution that the surrounding ocean floor.

The Countries Mapping the Ocean Floor

The closer an area is to a population center, the higher the likelihood it has been mapped. That said, many countries still have a long way to go before they have a clear picture of their land beneath the waves.

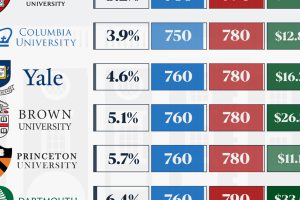

Here is a snapshot of how far along countries are in their subsea mapping efforts:

| Countries/territories | Size of Exclusive Economic Zone* (EEZ) | Percentage of EEZ mapped |

|---|---|---|

| Japan | 1,729,501 mi² (4,479,388 km²) | 97.7% |

| United Kingdom | 2,627,651 mi² (6,805,586 km²) | 90.6% |

| Norway | 920,922 mi² (2,385,178 km²) | 81.9% |

| New Zealand | 1,576,742 mi² (4,083,744 km²) | 74.0% |

| United States | 4,382,645 mi² (11,351,000 km²) | 69.9% |

| Australia | 3,283,933 mi² (8,505,348 km²) | 64.9% |

| Iceland | 291,121 mi² (754,000 km²) | 49.9% |

| South Africa | 592,874 mi² (1,535,538 km²) | 39.5% |

| Canada | 2,161,815 mi² (5,599,077 km²) | 38.8% |

| Samoa | 49,401 mi² (127,950 km²) | 34.6% |

| South Korea | 183,579 mi² (475,469 km²) | 28.3% |

| Taiwan | 32,135 mi² (83,231 km²) | 26.3% |

| Argentina | 447,516 mi² (1,159,063 km²) | 22.6% |

| Cook Islands | 756,770 mi² (1,960,027 km²) | 29.0% |

| Phillippines | 614,203 mi² (1,590,780 km²) | 16.7% |

| China | 338,618 mi² (877,019 km²) | 11.4% |

| Madagascar | 473,075 mi² (1,225,259 km²) | 5.5% |

| Bangladesh | 45,873 mi² (118,813 km²) | 3.3% |

| Thailand | 115,597 mi² (299,397 km²) | 1.5% |

*An exclusive economic zone (EEZ) is the sea zone stretching 200 nautical miles (nmi) from the coast of a state.

Japan and the UK, which have the 5th and 8th largest EEZs respectively, are the clear leaders in mapping their ocean territory.

Piecing Together the Puzzle

Sometimes tragedy can have a silver lining. By the time the search for Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 concluded in 2014, scientists had gained access to more than 100,000 square miles of newly mapped sections of the Indian Ocean.

Of course, it will take a more systematic approach and sustained effort to truly map the world’s ocean floors. Thankfully, a project called Seabed 2030 has the ambitious goal of mapping the entire ocean floor by 2030. The organization is collaborating with existing mapping initiatives in various regions to compile bathymetric information (undersea map data).

It’s been said without hyperbole that we know more about the surface of Mars than we do about our own planet’s seabed, but thanks to the efforts of Seabed 2030 and other initiatives around the world, puzzle pieces are finally falling into place.