What Drives Long-Term National Debt Growth?

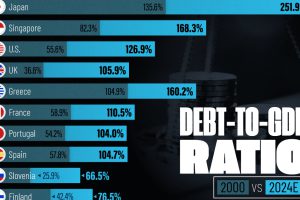

With the current 106% debt-to-GDP ratio, there’s no doubt that today’s government debt is high. The last time the United States reached this mark, it was during the aftermath of WWII in the late 1940s.

But despite nearly historic debt levels, it does not seem that the national debt is a key issue for most citizens and groups. What drives this accumulation of debt in the long run, and at what point does the debt level become so high that it becomes an undeniable and critical issue for the country?

Today’s infographic comes from the Peter G. Peterson Foundation, a NYC-based group that focuses on educating people about the fiscal challenges of growing government debt. The graphic illustrates the main factors driving the debt upwards, as well as the potential impact down the road.

Rising Temperatures

The trouble with debt is that it delays today’s challenges well into the future, making it a tempting short-term solution when other things aren’t working. However, over time, that burden increases steadily, and the situation quickly represents the “frog and boiling water” parable.

So what’s raising the temperature of that water?

Right now, the aging of the Baby Boomers is a key factor, and the amount of people receiving social security benefits will swell from 62 million to 88 million people by 2035. At the same time, Medicare’s hospital trust fund will run out of money by 2029, and the program will only remain solvent until 2034.

Whether it’s the growing enrollment in these programs or the rapidly escalating costs of healthcare itself, more money will be put towards Social Security and healthcare over the coming years.

By about 2045, government spending on major health programs will nearly double in size to greater than 9% of GDP.

Boiling Water

Today, interest on the debt is equal to about 1.4% of GDP.

However, if the projected pace is maintained, it’s anticipated that interest payments could be equal to 6.2% of GDP by 2047 – this is roughly 2x the average annual amount the federal government spends on education, infrastructure, and R&D combined.

As economists will point out, the government controls the monetary supply and can easily “print” money to make these payments. This is absolutely true, but it also creates an array of other problems such as inflation and increasing distrust in the monetary system.

Though this boiling point looms further down the road, having a plan to cool the temperature (or to jump out of the water) could be a prudent one to keep in our back pockets.