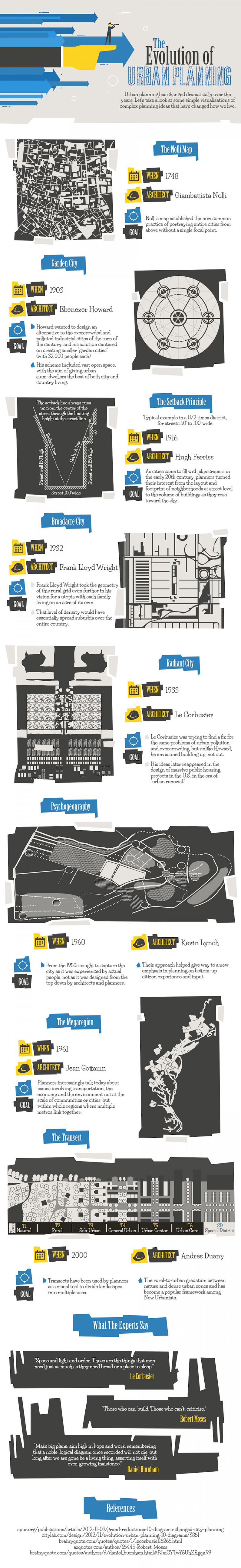

Urban planning has been around for as long as cities have existed, but the 20th century saw a number of bold ideas that radically changed the make-up of our urban centers.

From garden cities to psychogeography, today’s infographic by Konstantin von der Schulenburg is an informative overview of the modern movements and ideas that shaped urban planning.

The Evolution of Urban Planning

Urban planning has changed a lot over the centuries. Early city layouts revolved around key elements such as prominent buildings (e.g. cathedrals, monuments) and fortification (e.g. city walls, castles).

As cities grew larger, they also became more unpleasant. Here are some key ideas from architects and planners who sought tame the unruly urban beast.

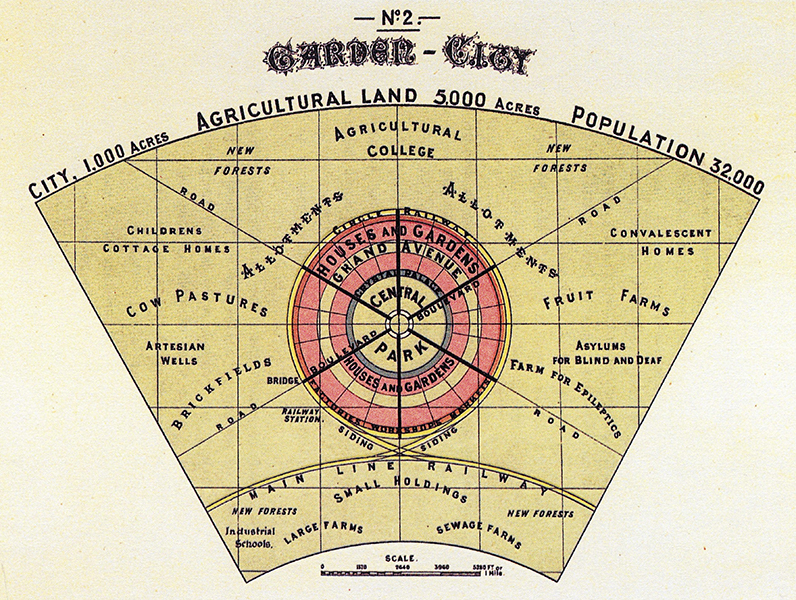

Garden City

At the dawn of the 20th century, cities were experiencing big population growth.

The Garden City concept – devised by the English planner Ebenezer Howard – sought to solve urban overcrowding and poor quality of life by creating smaller, master-planned communities on the outskirts of the larger city. The city would be structured around concentric circles of land use and include a sizeable park and greenbelt. Greenbelts were a revolutionary idea at the time and are still widely appreciated to this day.

Setback Principle

Early 1900s Manhattan had a population density of nearly 600 people per hectare and the skyscraper boom was in full swing. As buildings grew taller, the already crowded city was becoming a dark and claustrophobic place. To combat this, New York enacted the first citywide zoning code ever in the U.S. to help preserve some daylight on city streets. Setbacks had an immediate and lasting impact on Manhattan’s skyline, as seen today in landmarks such as the Empire State and Chrysler buildings.

Broadacre City

If there is a true antithesis for today’s urbanism, then the suburban brainchild of Frank Lloyd Wright is surely it. Broadacre City was a thought experiment that envisioned decentralized communities that would sprawl across a lush, bucolic landscape. That vision stood in stark contrast to frenetic, exhaust-choked cities of the 1940s, which resembled “fibrous tumor(s)” according to Wright.

Though Broadacre City was never built verbatim, Wright’s rejection of the American city came to life in the form of suburbs and strip malls from sea to shining sea.

La Cité Radieuse

In the wake of World War II, France was searching for solutions to house its population – nearly 20% of all French buildings were either destroyed or seriously damaged – and world renowned architect, Le Corbusier, was one of the architects selected by the French government to construct new, high-density housing.

When La Cité Radieuse (Radiant City) was completed in 1952, it kicked off a media frenzy. Indeed, Le Corbusier is credited with pioneering the Modernist style of architecture that became wildly popular around the world during that time.

While Le Corbusier’s thoughtful residential buildings have stood the test of time, not all projects inspired by the style shared the same fate. For example, when governments in Europe and the United States looked to provide cheap, high-density housing to low income families, the stark tower blocks they built often had the unintentional effect of ghettoizing their inhabitants.

The Megaregion

As cities within close proximity grow and merge together, finding a way to make them work as a connected economic and social unit is a key strategy for becoming more competitive on the global stage.

Jean Gottman, a French geographer, recognized this megaregion trend early on in the Northeast region of the United States. His seminal 1961 study, Megalopolis: The Urbanized Northeastern Seaboard of the United States, outlined the extraordinary dynamics that shaped America’s largest urban corridor.

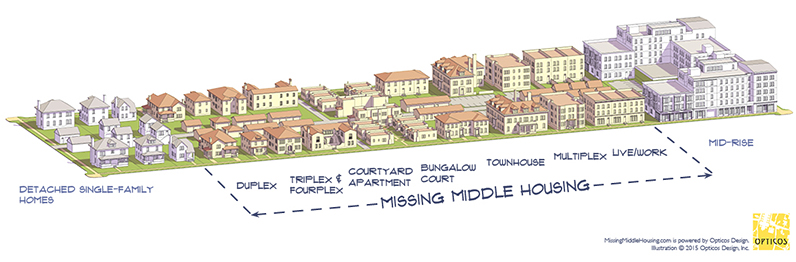

The Transect

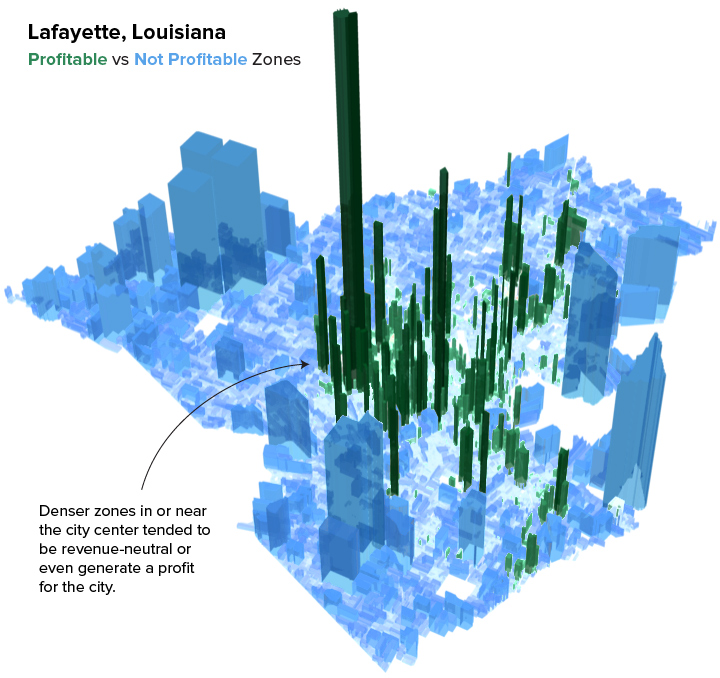

In North America, many cities have a stark divide between urban and suburban areas – a gap known as “the missing middle”. New urbanists seek to create more dense residential development, particularly in walkable, transit-accessible areas.

This new form of city planning isn’t just cosmetic, it may help save cities from bloated infrastructure costs. Recent research into the tax efficiency (property tax revenues vs. infrastructure maintenance costs) of a variety of American cities and found that walkable urban districts tended to be revenue-positive – in effect, subsidizing surrounding low-density areas.

Next Stop: Smart Cities

In the era of big data, the future of our physical spaces may be defined more by bytes than bricks.

City governments have been collecting big picture data for planning in transportation and zoning for some time, but new technology allows for the capture of even more granular data. Cities can now measure everything from noise pollution to wastewater volume, and this can have a big impact on spending efficiency and overall quality of urban spaces.

It’s almost like a FitBit for the city.

– Stuart Cowan, chief scientist, Smart Cities Council

A prominent section of waterfront in Toronto, Canada, is about to become a testing ground for this concept. The partnership between a government agency and Sidewalk Labs, a division of Alphabet, will produce an urban district that fully integrates technology and data collection into its design.

If the project is successful, it may influence the way future “smart” neighborhoods are constructed.