By the turn of the millennium, China was the sixth most productive nation in the world with a GDP comparable with France or Italy at US$1.2 trillion.

Economic growth didn’t stop there, and GDP increased ten-fold over the last fifteen years to surpass US$10 trillion. In “real” terms using PPP, China is now actually the largest economy in the world.

The rest of the world has benefited extensively from China’s coming out party. Cheap products flooded the shelves of the developed world, and China bought the world’s raw materials when no one else wanted them. Unfortunately, every good time must come to an end.

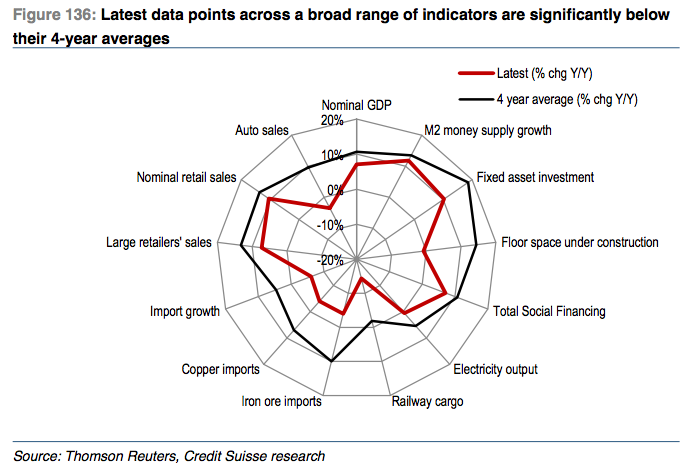

It hasn’t exactly been a secret that China’s economy has been slowing. The above radar graph from a research note by Credit Suisse shows that the economic news out of China has been tough to swallow as of late. Today, China rattled global markets even further by announcing a devaluation of the yuan by 1.9% to combat poor exports, which fell by 8.3% in July. This is the country’s largest currency devaluation since 1994.

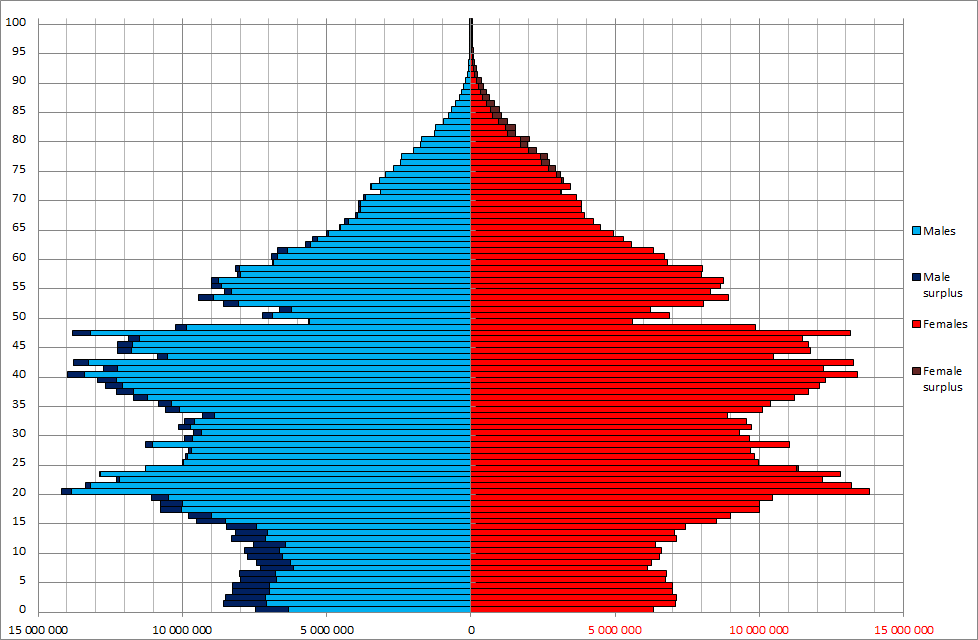

The real problem for China is far more entrenched: the country’s demographics have been a ticking timebomb for decades. The one-child policy meant that at some point in the future, the country would have an aging population that could not be replaced in the workforce.

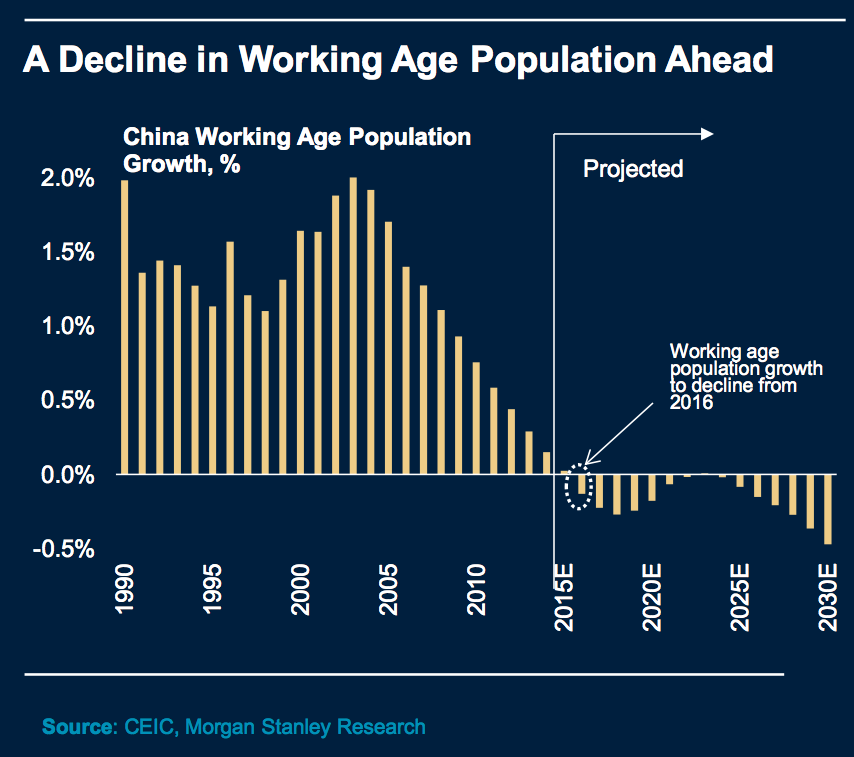

Unfortunately these demographic headwinds are now in full gear now and they are hitting China at the worst possible time. The size of China’s working population is set to begin declining.

Here’s a more in-depth look at China’s population pyramid from the 2010 census. Note that those who are 15 years old are now 20, and you will see that there are not many young people to enter the workforce, as well as the fact that there is an overabundance of males in the country (a separate demographic issue).

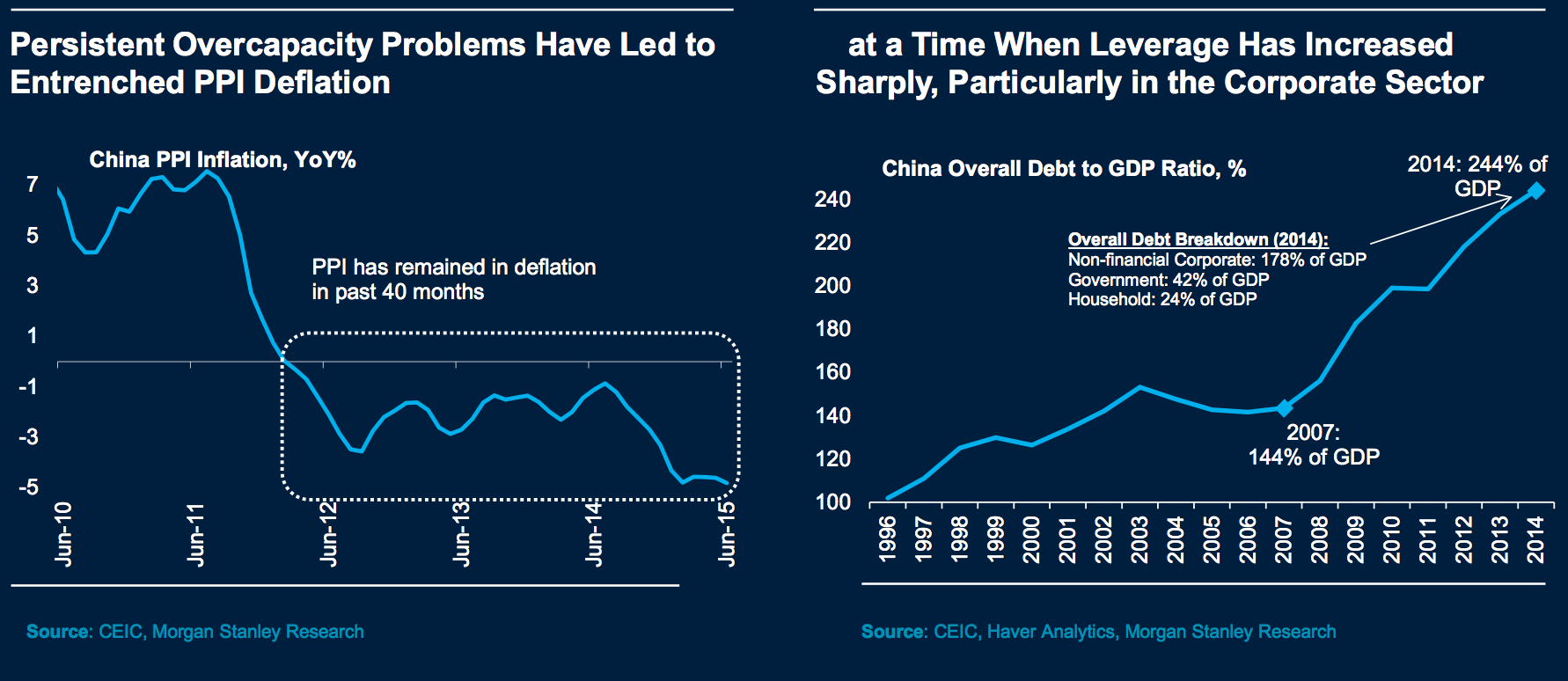

As the easy fuel for growth runs out, companies have sought to increase productivity by other means. Debt has soared for non-financial corporations in the country.

In the long run, growth is a function of changes in labour, capital and productivity. The Chinese growth engine is now sputtering: there is a shortage of young people in the workforce, exports are decreasing, investment has topped out, and its soaring debt will surely impede future growth.

We must now ask (and answer) the question: When Will India be the Next China?