Slices of the Pie: Mapping Territorial Claims in Antarctica

For the 55% of the world’s population who reside in cities, land is viewed as a precious commodity—every square foot has a value attached to it. As the global population continues to rise toward the eight billion mark, it can seem like humans have laid claim to every available corner of the earth.

While this is mostly true, there is one place on the planet that is vast, empty, and even partially unclaimed: Antarctica.

Today’s map, originally created by the CIA World Factbook, visualizes the active claims on Antarctic territory, as well as the location of many permanent research facilities.

The History of Antarctic Territorial Claims

In the first half of the 20th Century, a number of countries began to claim wedge-shaped portions of territory on the southernmost continent. Even Nazi Germany was in on the action, claiming a large swath of land which they dubbed New Swabia.

After WWII, the Antarctic Treaty system—which established the legal framework for the management of the continent—began to take shape. In the 1950s, seven countries including Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand, Norway, and the United Kingdom claimed territorial sovereignty over portions of Antarctica. A number of other nations, including the U.S. and Japan, were engaged in exploration but hadn’t put forward claims in an official capacity.

| Territorial claims in Antarctica | Territory name | Area of claim |

|---|---|---|

| 🇦🇺 Australia | Australian Antarctic Territory | 3,663,915 mi² (5,896,500 km²) |

| 🇳🇴 Norway | Queen Maud Land | 1,677,702 mi² (2,700,000 km²) |

| 🇬🇧 United Kingdom | British Antarctic Territory | 1,062,171 mi² (1,709,400 km²) |

| 🇦🇷 Argentina | Argentine Antarctica | 908,194 mi² (1,461,597 km²) |

| 🇨🇱 Chile | Chilean Antarctic Territory | 776,874 mi² (1,250,258 km²) |

| 🇳🇿 New Zealand | Ross Dependency | 279,617 mi² (450,000 km²) |

| 🇫🇷 France | Adélie Land | 268,432 mi² (432,000 km²) |

Despite the remoteness and inhospitable climate of Antarctica, the idea of claiming such large areas of landmass has proven appealing to countries. Even the smallest claim on the continent is equivalent to the size of Iraq.

A few of the above claims overlap, as is the case on the Antarctic Peninsula, which juts out geographically from the rest of the continent. This area is less remote with a milder climate, and is subject to claims by Argentina, Chile, and the United Kingdom (which governs the nearby Falkland Islands).

Interestingly, there is still a large portion of Antarctica that remains unclaimed today. Just east of the Ross Ice Shelf lies Marie Byrd Land, a vast, remote territory that is by far the largest unclaimed land area on Earth.

While Antarctica has no official government, it is administered through yearly meetings known as the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meetings. These meetings involve a number of stakeholders, from member nations to observer organizations.

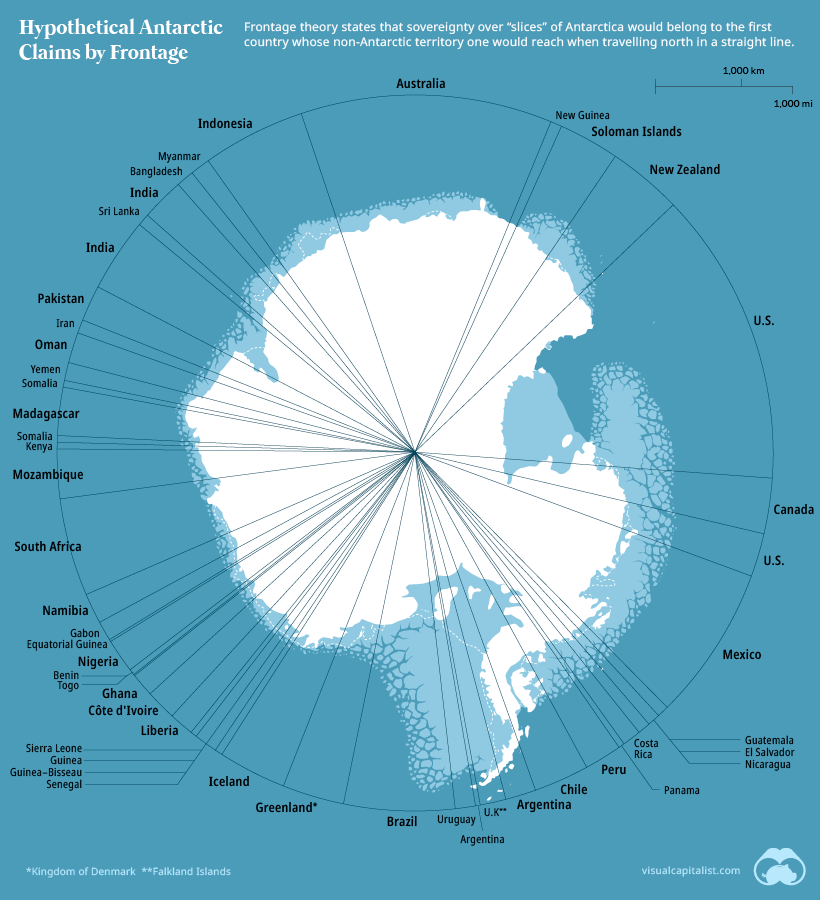

Frontage Theory: Another Way to Slice it

Of course, critics could argue that current claims are arbitrary, and that there is a more equitable way to partition land in Antarctica. That’s where Frontage Theory comes in.

Originally proposed by Brazilian geopolitical scholar Therezinha de Castro, the theory argues that sectors of the Antarctic continent should be distributed according to meridians (the imaginary lines running north–south around the earth). Wherever straight lines running north hit landfall, that country would have sovereignty over the corresponding “wedge” of Antarctic territory.

The map below shows roughly how territorial claims would look under that scenario.

While Brazil has obvious reasons for favoring this solution, it’s also a thought experiment that produces an interesting mix of territorial claims. Not only do nearby countries in Africa and South America get a piece of the pie, but places like Canada and Greenland would end up with territory adjacent to both of the planet’s poles.

Leaving the Pie Unsliced

Thanks to the Antarctic Treaty, there is no mining taking place in Antarctica, and thus far no country has set up a permanent settlement on the continent. Aside from scattered research stations and a few thousand researchers, claims in the region have a limited impact.

For the near future at least, the slicing of the Antarctic pie is only hypothetical.