Ranked: The Social Mobility of 82 Countries

It’s an unfortunate truth that a person’s opportunities can be partially tethered to their socioeconomic status at birth.

Although winning or losing the “birth lottery” will continue to shape the lives of generations to come, climbing the socioeconomic ladder is possible. However, it boils down to what opportunities people are afforded in the country they live in.

Today’s chart pulls data from the inaugural Global Social Mobility report produced by the World Economic Forum. The report ranks 82 countries according to their performance across five key pillars: healthcare, education, technology access, working conditions, and social protection.

While most countries aim to create a level playing field, which places best live up to this lofty and challenging mission?

The Spectrum of Social Mobility

Social mobility refers to the movement of individuals either up or down the socioeconomic ladder relative to their current standing, such as a low-income family moving up to become a part of the middle class.

Countries with high levels of social mobility exhibit lower levels of income inequality and provide more equally shared opportunities for its citizens across each of the five pillars.

Here is how all 82 countries rank, according to the report:

| Ranking | Countries | Index Score |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | Denmark | 85.2 |

| #2 | Norway | 83.6 |

| #3 | Finland | 83.6 |

| #4 | Sweden | 83.5 |

| #5 | Iceland | 82.7 |

| #6 | Netherlands | 82.4 |

| #7 | Switzerland | 82.1 |

| #8 | Belgium | 80.1 |

| #9 | Austria | 80.1 |

| #10 | Luxembourg | 79.8 |

| #11 | Germany | 78.8 |

| #12 | France | 76.7 |

| #13 | Slovenia | 76.4 |

| #14 | Canada | 76.1 |

| #15 | Japan | 76.1 |

| #16 | Australia | 75.1 |

| #17 | Malta | 75.0 |

| #18 | Ireland | 75.0 |

| #19 | Czech Republic | 74.7 |

| #20 | Singapore | 74.6 |

| #21 | United Kingdom | 74.4 |

| #22 | New Zealand | 74.3 |

| #23 | Estonia | 73.5 |

| #24 | Portugal | 72.0 |

| #25 | Korean Republic | 71.4 |

| #26 | Lithuania | 70.5 |

| #27 | United States | 70.4 |

| #28 | Spain | 70.0 |

| #29 | Cyprus | 69.4 |

| #30 | Poland | 69.1 |

| #31 | Latvia | 69.0 |

| #32 | Slovak Republic | 68.5 |

| #33 | Israel | 68.1 |

| #34 | Italy | 67.4 |

| #35 | Uruguay | 67.1 |

| #36 | Croatia | 66.7 |

| #37 | Hungary | 65.8 |

| #38 | Kazakhstan | 64.8 |

| #39 | Russian Federation | 64.7 |

| #40 | Bulgaria | 63.8 |

| #41 | Serbia | 63.8 |

| #42 | Romania | 63.1 |

| #43 | Malaysia | 62.0 |

| #44 | Costa Rica | 61.6 |

| #45 | China | 61.5 |

| #46 | Ukraine | 61.2 |

| #47 | Chile | 60.3 |

| #48 | Greece | 59.8 |

| #49 | Moldova | 59.6 |

| #50 | Vietnam | 57.8 |

| #51 | Argentina | 57.3 |

| #52 | Saudi Arabia | 57.1 |

| #53 | Georgia | 55.6 |

| #54 | Albania | 55.6 |

| #55 | Thailand | 55.4 |

| #56 | Armenia | 53.9 |

| #57 | Ecuador | 53.9 |

| #58 | Mexico | 52.6 |

| #59 | Sri Lanka | 52.3 |

| #60 | Brazil | 52.1 |

| #61 | Philippines | 51.7 |

| #62 | Tunisia | 51.7 |

| #63 | Panama | 51.4 |

| #64 | Turkey | 51.3 |

| #65 | Colombia | 50.3 |

| #66 | Peru | 49.9 |

| #67 | Indonesia | 49.3 |

| #68 | El Salvador | 47.4 |

| #69 | Paraguay | 46.8 |

| #70 | Ghana | 45.5 |

| #71 | Egypt | 44.8 |

| #72 | Laos | 43.8 |

| #73 | Morocco | 43.7 |

| #74 | Honduras | 43.5 |

| #75 | Guatemala | 43.5 |

| #76 | India | 42.7 |

| #77 | South Africa | 41.4 |

| #78 | Bangladesh | 40.2 |

| #79 | Pakistan | 36.7 |

| #80 | Cameroon | 36 |

| #81 | Senegal | 36.0 |

| #82 | Côte d’Ivoire | 34.5 |

There are a number of countries that set an example for social mobility that others can follow.

The Mobility Medal Winners

All of the countries in the top 10 are European, but it is the Nordic countries that sit comfortably at the top of the ranks.

Denmark holds the title for the most socially mobile country in the world, boasting an index score of 85.2. If a person is born into a low-income family in Denmark, the WEF estimates it would take two generations to reach a median income. In contrast, someone in Brazil or South Africa would take nine generations at the current pace of growth.

As one of the few non-European countries in the top 20, Canada also performs well across the majority of pillars, but similarly to Denmark, it could improve in the area of lifelong learning which includes providing support for the unemployed and teaching digital skills.

The Least Socially Mobile Countries

Developing country Côte d’Ivoire sits at the bottom of the ranks, with an index score of just 34.5. As a nation once ravaged by internal conflict and turbulent economic shifts, the resulting poverty rate remains high at 46.3%.

While the government has made improvements to its basic social services, the country falls behind on categories like access to education and fair wages, and retains the highest gender inequality rate in the world.

Despite a significant decrease in the percentage of people living in absolute poverty, India ranks low on the index in 76th place. Structural reform is required across all pillars if India is to increase its score, especially in relation to fair wages and education.

Why Invest in Social Mobility?

According to the report, most economies are far from providing fair conditions for their citizens to thrive, with the greatest challenges ranging from lack of social protection and low wages to poor lifelong learning systems.

Countries that fail to invest in the key pillars of social mobility could experience damaging consequences for governments and citizens alike:

- Precarity (the unpredictability of living without secure and well-paid employment)

- Perceived loss of identity and dignity

- Weakening social fabric

- Eroding trust in institutions

- Disenchantment with political processes

Aside from the social returns, the economic impact of investing in the right blend of social mobility pillars could be substantial.

Calculating the True Cost

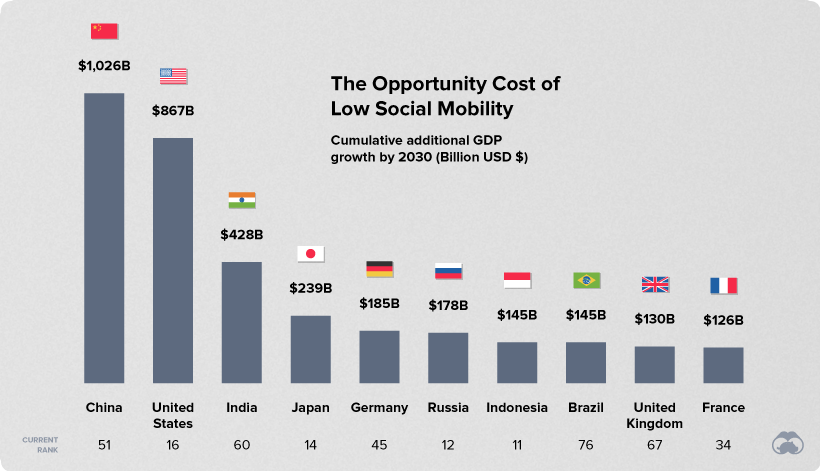

The report dives into the opportunity cost of low social mobility and finds that if each country increased its score by just 10 index points, it could result in an extra 4.41% of cumulative GDP growth for the global economy by 2030—equal to $5.1 trillion.

China alone could add $1 trillion of GDP growth by 2030 if a 10 point increase is achieved:

Although social mobility can act as an economic lever, many countries are struggling to provide the optimal conditions for their citizens to thrive. For those countries, globalization and technology may continue to exacerbate income inequality.

If countries are unable to create new social mobility pathways towards more inclusive economies, they risk being stuck in a cycle where inequality remains entrenched—and history continues to repeats itself.